Food and Drink: Regional Cuisine

British food is often reduced to a few signature dishes—fish and chips, Sunday roast, tea and crumpets—but the United Kingdom has a diverse culinary tradition. The national cuisine reflects local character the union’s constituent countries—England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland—along with myriad international influences from its long colonial history.

Common Foods

Wholesome, simple, and hearty, British cuisine is noted for its meat and vegetable dishes, savory puddings, pastries, pies, and of course, tea. Beer, particularly local ales, stouts, porters, and India pale ales, are not only beloved beverages, but an important part of British social life and pub culture. Unique dining practices include the full English breakfast and afternoon tea. Nowhere in the United Kingdom is more than 84 miles (135 kilometers) away from the coast, and seafood and fish play an important role in all regional cuisines.

Culinary Influences

Characteristic British stews and slow-cooked meats with sauces date back to the early medieval period—the Anglo-Saxons are said to have developed stewing and roasting techniques before mainland Europe. The Norman invasion in the 11th century gave the local cuisine a continental twist, as beef, mutton, and wine drinking became widespread. During the Renaissance, Britain rose to become a leading maritime power and established colonies around the world, which introduced new foods and cooking styles, notably tea and exotic spices. Industrialization in the 19th century brought about the first processed foods, which today are consumed widely in the form of convenience foods and fast food. British cuisine suffered a loss of prestige in the 20th century, gaining a reputation for being bland and boring. These negative associations arose due to strict rationing schemes imposed by the government during both world wars and persisted for up to a decade after each conflict.

Culinary Renaissance

That said, British cuisine has undergone a kind of rebirth in the past decades under the banner of modern British cooking, with a return to farm-to-table ingredients, international flavors, and heritage recipes. In this increasingly multicultural country, immigration also has expanded the repertoire of the average home cook, infusing new flavors into the cuisine. Indian-inspired chicken tikka masala, for instance, has become so popular that it is often cited as the British national dish. While British tastes may be becoming more international, the sun will probably never set on traditional standby recipes.

Culinary Regions of the United Kingdom

England

England is the geographic and cultural center of the United Kingdom, and English food is often conflated with British, as many of the representative dishes of the national cuisine come from England. English cuisine was codified in the 15th century in The Forme of Cury (The Method of Cooking), a cookbook written by King Richard II’s cooks. While the title seems to anticipate the importance of Indian-style “curry” in modern British cuisine, this early cookbook displays a wide range of local ingredients, such as whale and game, as well as influences from Spanish, French, and Italian cooking, suggesting that English dishes have long been locally rooted, and with an international twist.

The Earl of Sandwich is credited with inventing the sandwich when he asked his servant to bring him his meat wedged between two slices of bread so he could continue playing his card game. Traditional English foods include cheeses like Cheddar and Stilton, stews, roasted meats and game, and savory pies. Dishes tend to emphasize a balance of sweet and sour flavors, with a preference for fresh herbs over dried spices.

Yorkshire pudding. From the north of England, these baked egg-flour dough turnovers are served with the traditional Sunday roast.

Cornish pasties. From the region of Cornwall, pasties are savory baked pastries filled with beef, potato, or turnips, and shaped into a characteristic semi-circular form with crimped edges. Easy to eat by hand, pasties became popular during the 19th century, when they were sold to blue-collar workers as a quick meal on the way to their shift at the factory.

Lancashire hotpot. The industrial northwest region of Lancashire industrialized quickly in the 19th century, and with both men and women spending long hours in the factories, the Lancashire hotpot—a hodgepodge of mutton, onion, and sliced potato—could be left at home to cook on low heat and would be ready for dinner later that night.

Jellied eels. Boiled in a spiced stock, the eels are left to cool and set, resulting in a jelly that is served cold. The recipe comes from east London, where poor residents have fished plentiful eels out of the Thames River for centuries.

Stargazy pie. Also from Cornwall, this is a baked savory pie of sardines in egg and potato, covered with a pastry crust. The fish heads and tails protrude out of the piecrust, giving them the appearance of gazing upwards toward the stars.

Scotland

Since the Middle Ages, Scots have fiercely fought against incursions from the neighboring English, and although the English language and culture eventually infiltrated the northern peninsula of Great Britain, the Scots hold fast to their national identity, which is reflected in their unique culinary traditions.

Surrounded by ocean on three sides, Scotland’s interior is also filled with rivers and freshwater lakes, making fish and seafood important components of the local cuisine. Barley, root vegetables, and oats grow well in the cool climate. The arrival of the Vikings from Scandinavia in the 8th century introduced cooking and preservation techniques such as salting and smoking, which are more prominent than in other regional cuisines of Great Britain. Wild game from the Scottish Highlands was an important source of protein. Due to its relative isolation from the rest of Europe, traditional Scottish cuisine uses few imported spices, relying instead on local herbs and cooking techniques such as stewing to impart flavor. Scotland is also famous for its malted barley whisky—so famous, in fact, that the beverage is known worldwide as Scotch.

Haggis. This savory pudding is a signature Scottish dish containing a trio of sheep heart, liver, and lungs, with onion, oats, and spices, all encased in sheep stomach. Although the ingredients may not sound immediately appealing to some, the dish is praised for its fine texture and nutty flavor. Haggis is traditionally served with neeps and tatties—sides of mashed rutabaga and potatoes.

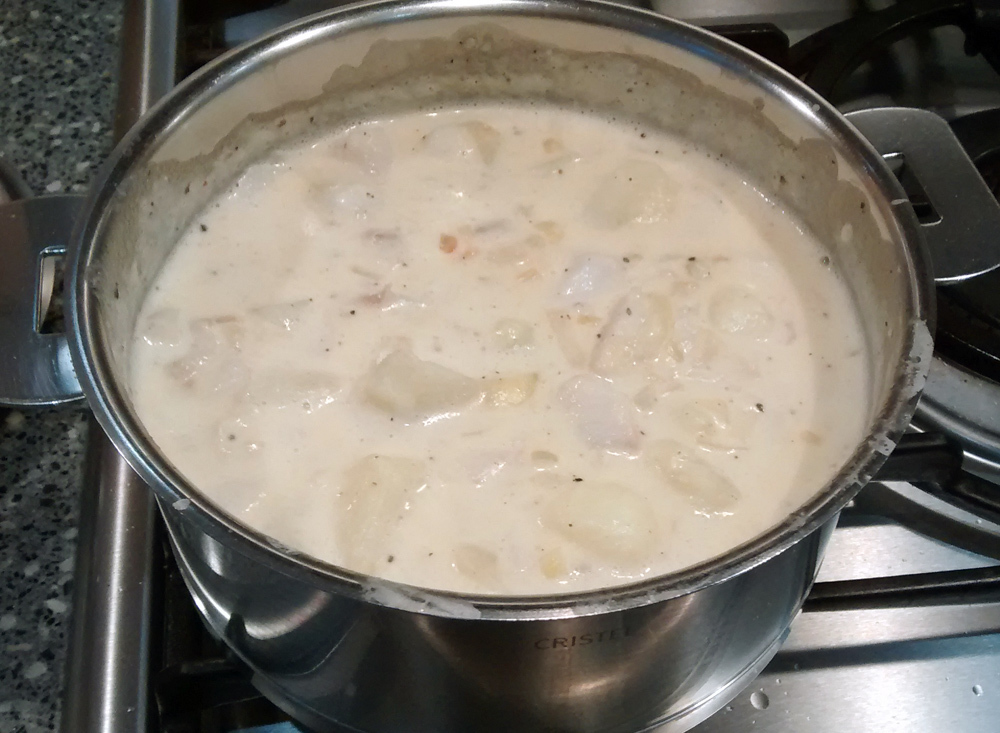

Cullen skink. A thick chowder of smoked haddock with potatoes and onions, this hearty dish is both an everyday meal in the northeast coast, where it originates, and part of high-end Scottish cuisine. Cullen skink is often served as the soup course at formal banquet dinners.

Cock-a-leekie soup. This clear-broth stew is made with peppered chicken and simmered leeks. It is considered the signature Scottish soup and was famously one of two soups served at lunch on the Titanic the last day of its ill-fated voyage.

Mince and tatties. Mince refers to a mix of pan-fried ground beef, onion, and carrots that is thickened with stock and flour. Tatties are simply mashed potatoes. Mince and tatties are a mainstay of cafeteria dining and quick family dinners in Scotland. It is considered the country’s most popular dish, with a third of Scots reporting that they eat it at least once a week.

Shortbread. Popular throughout the United Kingdom, shortbread is a sweet Scottish biscuit made from one part sugar, two parts butter, and three parts flour. The recipe dates from the medieval period, but was popularized in the 16th century by Mary, Queen of Scots.

Wales

Wales means “foreigner” in proto-Germanic, a term used by early Germanic tribes to describe the Celtic inhabitants of the southwestern region of the island of Great Britain. For much of their history, the Welsh lived in relative isolation from the rest of the island and Europe, surviving in the cold, mountainous landscape by raising cattle and sheep, fishing, and mining. Welsh cuisine reflects this rural, peasant history and proud independent cultural and ethnic identity.

Due to the terrain and weather, much of the land is not suitable for agriculture. Historically, Celtic Welsh derived wealth from the number of cattle owned, making beef a rarity in the local cuisine. Cows were instead used for their milk, and dairy products are featured prominently in Welsh dishes. Mutton and fish are the main protein sources. Leeks, the national vegetable and emblem of Wales, cabbage, and oats grow well in the cool, damp climate.

Cawl. Considered Wales’ national dish, cawl is a meat and seasonal vegetable soup. It’s an old recipe, dating to the times when the cauldron was left to cook on the embers of the fire while the family was out working the fields. This one-pot recipe is served in two courses: the broth-based soup as the first, and the boiled meat and vegetables as the main.

Welsh rarebit. A savory cheese sauce spiced with ale, mustard, and pepper is poured over toasted bread and allowed to cool before serving. Thought to be a corruption of the word “rabbit,” rarebit does not contain any rabbit or meat of any kind, only cheese and bread.

Glamorgan sausage. Made of cheese with leek and spring onion, this sausage contains no meat at all. It is rolled into a sausage shape, coated in breadcrumbs, and fried. Glamorgan sausage was a common dish among the rural poor, and it experienced a resurgence of popularity during World War II, when meat was rationed.

Bara brith. Translated as “speckled bread,” this spiced sweet loaf is filled with dried raisins and currents and is served with famous Welsh butter at afternoon tea.

Laverbread. Laver is an edible form of purple seaweed, and in Wales, boiled laver is pureed into a gelatinous paste, and is then either coated in oatmeal and fried, or added to bread dough. Served with bacon and cockles, laverbread is part of the traditional Welsh breakfast. The Welsh actor Richard Burton once described the nutritious delicacy as the “Welshman’s caviar.”

Northern Ireland

Northern Irish cuisine has much in common with Irish cuisine as a whole, as the political division between Northern Ireland, which belongs to the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland is relatively young—until 1948, the entire island was under the Crown. For centuries, English colonization impoverished the island, and the majority of the Irish lived on humble meals of potatoes and bread. Traditional Irish cuisine thus tends to be simple and rustic, emphasizing stews, pasties, root vegetables, soda bread, and of course, Guinness, a dark dry stout. Northern Ireland contributed its famously hearty breakfast, the Ulster fry, and various fish dishes to British cuisine.

Ulster Fry. The northern province of Ulster extends into both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Despite their political differences, both share a common breakfast tradition: the Ulster fry. Bacon, eggs, tomato, and grilled soda or potato bread make for a hearty breakfast.

Potato boxty. This Irish potato pancake is a northern specialty. Sometimes called potato bread, boxty is a loaf of one-part mashed potato and one-part grated potato mixed with flour and egg and fried on a griddle. It means “poor house bread” in the local dialect, reflecting the peasant origins of this dish.

Ardglass potted herring. A specialty of the Northern Irish capital of Belfast, potted herring is a casserole of baked herring flavored with malt vinegar and bay leaf.

Article written for World Trade Press by Carly K. Ottenbreit.

Copyright © 1993—2024 World Trade Press. All rights reserved.

United Kingdom

United Kingdom